Schema Therapy 1 is an integrative model of psychotherapy developed by American psychologist and founder of the Schema Therapy Institute, Jeffrey E. Young that combines proven cognitive and behavioural techniques with other widely practiced therapies. The main goals of Schema Therapy are to help patients strengthen their Healthy Adult mode, weaken their Maladaptive Coping Modes so that they can get back in touch with their core needs and feelings, heal their early maladaptive schemas to break schema-driven life patterns, and eventually to get their core emotional needs met in everyday life.

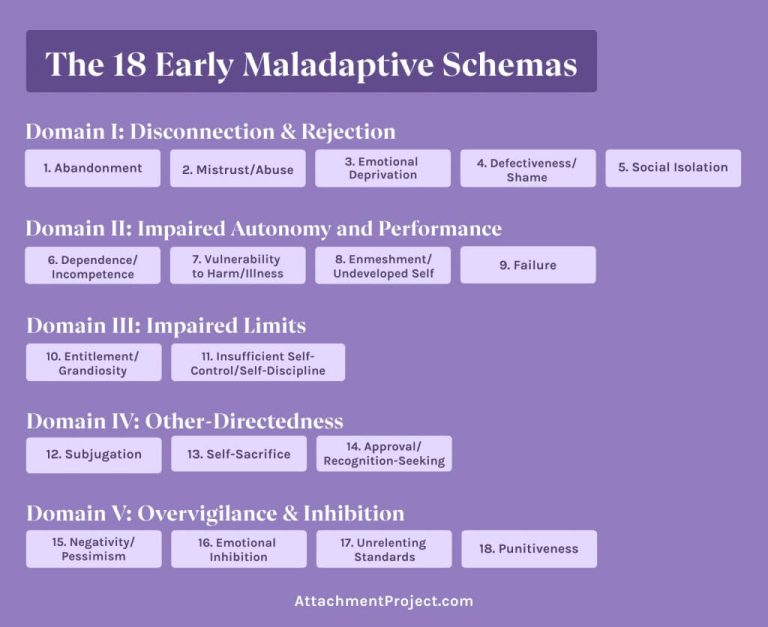

The 18 Early Maladaptive Schemas are self-defeating, core themes or patterns that we keep repeating throughout our lives.

Schemas

Young’s schema therapy proposes eighteen early maladaptive schemas that show up in adulthood as dysfunctional life themes (also called “buttons” or “life traps”). They are considered early maladaptive schemas because they derive from childhood and adolescent experiences where fundamental needs are not adequately met, which interferes with healthy and stable development. Schemas are beliefs or cognitions, involving emotional and bodily sensations, along with biological elements such as temperament.

We all have schemas 2, typically more than one, formed in response to naturally imperfect and sometimes traumatic early life experiences. In many cases, noxious events such as abuse, neglect, abandonment, chaos, or excessive control cause schemas to fasten to a child’s emotional makeup. This, in combination with biological predisposition, or temperament, ultimately sculpts our personality. When schemas are triggered (“He really pushed my buttons”), we may become flooded with uncomfortable physical sensations and biased thoughts and engage in self-defeating behaviors.

The 18 Early Maladaptive Schemas 3:

- Domain 1: Disconnection and Rejection

Abandonment, Mistrust/Abuse, Emotional Deprivation, Defectiveness/Shame, Social Isolation - Domain II: Impaired Autonomy and Performance

Dependence/Incompetence, Vulnerability to Harm/Illness, Enmeshment/Undeveloped Self, Failure - Domain III: Impaired Limits

Entitlement/Grandiosity. Insufficient Self-Control/Self-Discipline - Domain IV: Other-Directedness

Subjugation, Self-Sacrifice, Approval/Recognition-Seeking - Domain V: Overvigilance and Inhibition

Negativity/Pessimism, Emotional Inhibition, Unrelenting Standards, Punitiveness

A Schema is an emotional belief, first formed in your childhood or adolescence, that carries an exaggerated realness and intensity under certain conditions, even if it’s dormant most of the time.

Schemas may be dormant for much of one’s life, only becoming activated by conditions that either mimic or challenge the unyielding beliefs embodied within them. These “truths,” which are the abiding content of the schema, have long been held and are difficult to refute. They are often connected with painful childhood memories, discreetly sheltered within the brain, and are experienced as visceral, meaning they are sensed (but not always sensible). Because they emerge outside of awareness and therefore aren’t based on the present, the profound and often exaggerated resonance of schemas frequently leads to self-defeating behavior patterns.

Schemas emerge outside of awareness and therefore aren’t based on the present, the profound and often exaggerated resonance of schemas frequently leads to self-defeating behavior patterns.

In her book Disarming the Narcissist: Surviving and Thriving with the Self-Absorbed 2, psychotherapist Wendy T. Behary highlights Jeffrey Young‘s Eighteen Early Maladaptive Schemas, which are:

1. Abandonment/instability.

The perceived instability or unreliability of significant others. The sense that they will not be able to provide emotional support, connection, strength, or practical protection because they are emotionally unstable and unpredictable (for example, prone to angry outbursts), unreliable, or erratically present; because they will die imminently; or because they will abandon you in favor of someone better.

2. Mistrust/abuse.

The expectation that others will hurt, abuse, humiliate, cheat, lie, manipulate, or take advantage. Usually the harm is perceived as intentional or the result of extreme negligence. May include feeling always cheated or getting the short end of the stick.

3. Emotional deprivation.

The expectation that others will not adequately meet your desire for normal emotional support. The major forms of deprivation are:

A. Deprivation of nurturance: absence of attention, affection, warmth, or companionship

B. Deprivation of empathy: absence of understanding, listening, self-disclosure, or mutual sharing of feelings

C. Deprivation of protection: absence of strength, direction, or guidance

4. Defectiveness/shame.

The feeling that you are defective, bad, unwanted, inferior, invalid, or unlovable if exposed. May involve hypersensitivity to criticism, rejection, and blame; self-consciousness, comparisons, and insecurity around others; or shame regarding your perceived flaws. These flaws may be private (for example, selfishness, angry impulses, or unacceptable sexual desires) or public (such as undesirable physical appearance or social awkwardness).

5. Social isolation/alienation.

The feeling that you are isolated from the rest of the world, different from other people, and/or not part of any group or community.

6. Dependence/incompetence.

The belief that you are unable to handle everyday responsibilities in a competent manner without considerable help from others (for example, take care of yourself, solve daily problems, exercise good judgment, tackle new tasks, or make good decisions). Often feels like helplessness.

7. Vulnerability to harm or illness.

Exaggerated fear of imminent and unpreventable catastrophe. Fears focus on one or more of the following: medical catastrophes or illnesses; emotional catastrophes, such as “going crazy”; or external catastrophes, such as elevators collapsing, criminal attack, airplane crashes, or earthquakes.

8. Enmeshment/undeveloped self.

Excessive emotional involvement and closeness with one or more significant others (often parents) at the expense of individual identity or normal social development. You may believe you cannot survive or be happy without the constant support of the enmeshed other. You may feel smothered by or fused with others, a lack of sufficient individual identity, emptiness or without direction, or, in extreme cases, question your existence.

9. Failure.

The belief that you have failed, will inevitably fail, or are fundamentally inadequate in areas of achievement (such as school, career, or sports). Often involves beliefs that you are stupid, inept, untalented, ignorant, lower in status, less successful than others, and so on.”

10. Entitlement/grandiosity.

The belief that you are superior to others, entitled to special privileges, or not bound by normal social rules. Often involves insistence that you should be able to do or have whatever you want, regardless of what is realistic or reasonable, or regardless of the cost to others. An exaggerated focus on superiority (for example, being the most successful, famous, wealthy) to achieve power or control (not primarily attention or approval) is common. Sometimes includes excessive competitiveness or domination of others: asserting power, forcing a point of view, or controlling the behavior of others without empathy.

11. Insufficient self-control/self-discipline.

Difficulty or refusal to exercise sufficient self-control and tolerate frustration to achieve goals or restrain excessive emotions and impulses. In its milder form, you may tend to avoid discomfort—pain, conflict, confrontation, responsibility, or overexertion—at the expense of personal fulfillment, commitment, or integrity.

12. Subjugation.

Excessive surrendering of control to others—usually to avoid anger, retaliation, or abandonment. The major forms of subjugation are:

A. Subjugation of needs: suppression of your preferences, decisions, and desires

B. Subjugation of emotions: suppression of emotional expression, especially anger

Usually involves the perception that your desires, opinions, and feelings are not valid or important to others, and a tendency toward excessive compliance combined with hypersensitivity to feeling trapped. Generally leads to anger, which can lead to passive-aggressive behavior, outbursts of temper, psychosomatic symptoms, withdrawal of affection, and substance abuse.

13. Self-sacrifice.

Excessive focus on meeting the needs of others at the expense of your own gratification, most commonly to prevent causing others pain, avoid feeling selfish, or maintain a connection with others. Often results from an acute sensitivity to the pain of others. Sometimes leads to resentment and feeling your own needs are not being adequately met. (Overlaps with the concept of codependency.)

14. Approval seeking/recognition seeking.

Excessive emphasis on gaining approval, recognition, fitting in, or attention from others, at the expense of developing a secure and true sense of self. Your self-esteem is dependent primarily on the reactions of others rather than yourself. Sometimes includes an overemphasis on status, appearance, social acceptance, money, or achievement—as means of gaining approval, admiration, or attention (not primarily power or control). Frequently results in hypersensitivity to rejection or unsatisfying and inauthentic major life decisions.

15. Negativity/pessimism.

A pervasive, lifelong focus on the negative aspects of life (pain, death, loss, disappointment, conflict, guilt, resentment, unsolved problems, potential mistakes, betrayal, worry, and so on) while minimizing the positive. Usually includes exaggerated expectations—in a wide range of situations—that things will eventually go seriously wrong or will ultimately fall apart, even if they seem to be going well. Usually involves an inordinate fear of making mistakes that might lead to financial collapse, loss, humiliation, or being trapped in a bad situation. Because potential negative outcomes are exaggerated, chronic worry, vigilance, complaining, or indecision are common.

16. Emotional inhibition.

The excessive inhibition of spontaneous action, feeling, or communication—usually to avoid disapproval by others, feelings of shame, or loss of control. The most common areas of inhibition involve anger and aggression; positive impulses (such as joy, affection, sexual excitement, or play); difficulty expressing vulnerability or communicating freely about your feelings, needs, and so on; and excessive emphasis on reason over emotion.

17. Unrelenting standards/hypercriticalness.

The belief that you must strive to meet very high internalized standards of behavior and performance, usually to avoid criticism. Typically results in feelings of pressure or difficulty slowing down, and in hypercriticalness toward yourself and others. Involves significant impairment in pleasure, relaxation, health, self-esteem, sense of accomplishment, or satisfying relationships. Forms of unrelenting standards typically appear as:

A. Perfectionism, inordinate attention to detail, or an underestimate of your performance relative to the norm

B. Rigid rules and “shoulds” in many areas of life, including unrealistically high moral, ethical, cultural, or religious precepts

C. Preoccupation with time and efficiency, so that more can be accomplished

18. Punitiveness.

The belief that people should be harshly punished for making mistakes. Involves the tendency to be angry, intolerant, punitive, and impatient with people (including yourself) who do not meet your expectations or standards. Usually includes difficulty forgiving mistakes in yourself or others because of a reluctance to consider extenuating circumstances, allow for human imperfection, or empathize.

Typically when schemas are triggered, you are not aware of what is really happening, only of the feeling of danger or imminent threat based on a suggestive stimulus.

Like an infection, the schema doesn’t respond to the first round of practical interventions. You may ultimately—and frequently—find your negative expectations unwarranted but still be unable to halt the careening process once a schema is triggered. You may even recognize it as a vaguely familiar unease, reminiscent of something but unsure of its origins.

The goal is to distinguish genuine threats from schemas that distort your perceptions and responses. To do this, you need to make the implicit more explicit; you need to become aware of inner motivations in a way that is deeply felt, not just intellectually understood.

In combination with biological makeup2 , early experience can dramatically shape our impressions, beliefs, and responses vis-à-vis the world we live in. We are creatures of habit who gravitate toward the familiar, and our early maladaptive schemas can be like a boomerang leading us back to where we started. Understanding the finely honed mechanisms of the brain gives us an appreciation for how cumbersome change is, while also affirming that change is possible. For all of us, grasping and accepting the anatomical realities of memory and its associational tendencies can help mediate obstacles to change, like shame and self-blame.

Our brains are primed to launch protective missiles when an enemy is present, and in this case the schema is the enemy. Ironically, while seeking refuge from this predator, we often end up right back in its grip.

A lifetrap 4 is a pattern that starts in childhood and reverberates throughout life. It began with something that was done to us by our families or by other children. We were abandoned, criticized, overprotected, abused, excluded, or deprived—we were damaged in some way. Eventually the lifetrap becomes part of us. Long after we leave the home we grew up in, we continue to create situations in which we are mistreated, ignored, put down, or controlled and in which we fail to reach our most desired goals.

“Lifetraps determine how we think, feel, act, and relate to others. They trigger strong feelings such as anger, sadness, and anxiety. Even when we appear to have everything—social status, an ideal marriage, the respect of people close to us, career success—we are often unable to savor life or believe in our accomplishments.”

The technical term for a lifetrap is a schema. The concept of a schema comes from cognitive psychology. Schemas are deeply entrenched beliefs about ourselves and the world, learned early in life. These schemas are central to our sense of self. To give up our belief in a schema would be to surrender the security of knowing who we are and what the world is like; therefore we cling to it, even when it hurts us.

These early beliefs provide us with a sense of predictability and certainty; they are comfortable and familiar.

Sources:

- Jeffrey E. Young‘s Schema Therapy Institute 1

- Disarming the Narcissist: Surviving and Thriving with the Self-Absorbed 2

- The Attachment Project’s Early Maladaptive Schemas (EMS) Quiz 3

- Reinventing Your Life: The Breakthrough Program to End Negative Behavior and Feel Great Again by Jeffrey E. Young 4

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.