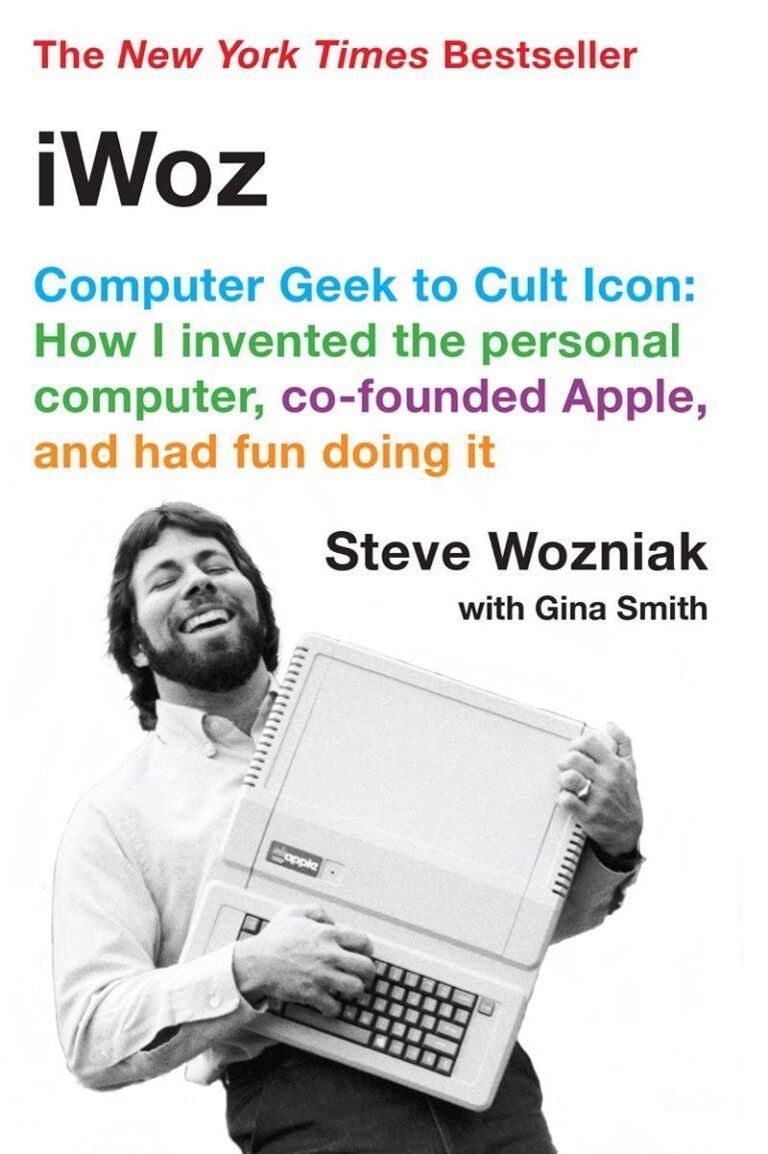

In iWoz: Computer Geek to Cult Icon: How I Invented the Personal Computer, Co-Founded Apple, and Had Fun Doing It, Steve Wozniak writes about the origin story of Apple, meeting his co-founder Steve Jobs, his upbringing, love for programming, and the values that has guided his decisions. He wrote the book to dispel some misconceptions about his relationship with Steve Jobs and feeling towards Apple.

Lucky Accident – Magazine

At about this time, there was another lucky accident. I found this article about computers in one of the old engineering journals my dad had hanging around. Back then, back in 1960, writing about computers wasn’t common at all. But what I saw was an article about the ENIAC and a picture of it. The ENIAC— which stood for Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer—was the first true computer by most people’s definition. It was designed to calculate bomb trajectories for the military during World War II. So it was designed back in the 1940s.

On Steve Jobs

I never had the courage to ask chip companies for free samples of what were then expensive chips. A year later I would meet Steve Jobs, who showed me how brave he was by scoring free chips just by calling sales reps. I could never do that. Our introverted and extroverted personalities (guess who’s which) really helped us in those days. What one of us found difficult, the other often accomplished pretty handily. Examples of that teamwork are all over this story.

Meeting Steve Jobs

I was four years ahead of him in school so I didn’t know him; he was closer to Bill Fernandez’s age. But one day Bill told me, “Hey, there’s someone you should meet. His name is Steve. He likes to do pranks like you do, and he’s also into building electronics like you are.”

So one day—it was daytime, I remember—Bill called Steve and had him come over to his house. I remember Steve and I just sat on the sidewalk in front of Bill’s house for the longest time, just sharing stories—mostly about pranks we’d pulled, and also what kind of electronic designs we’d done. It felt like we had so much in common. Typically, it was really hard for me to explain to people the kind of design stuff I worked on, but Steve got it right away. And I liked him. He was kind of skinny and wiry and full of energy.

Steve and I got close right away, even though he was still in high school, remember, and lived about a mile away in Los Altos. I lived in Sunnyvale. Bill was right—we two Steves did have a lot in common. We talked electronics, we talked about music we liked, and we traded stories about pranks we’d pulled. We even pulled a few together.

Bill was right—we two Steves did have a lot in common. We talked electronics, we talked about music we liked, and we traded stories about pranks we’d pulled. We even pulled a few together.

Patience

And thanks to all those science projects, I acquired a central ability that was to help me through my entire career: patience. I’m serious. Patience is usually so underrated. I mean, for all those projects, from third grade all the way to eighth grade, I just learned things gradually, figuring out how to put electronic devices together without so much as cracking a book. Sometimes I think, Man, I lucked out. It seems like I was just pointed in such a lucky direction in life, this early learning of how to do things one tiny little step at a time. I learned to not worry so much about the outcome, but to concentrate on the step I was on and to try to do it as perfectly as I could when I was doing it.

One Step at a time

Not everyone gets this in today’s engineering community, you know. Throughout my career at Apple and other places, you always find a lot of geeks who try to reach levels without doing the in-between ones first, and it won’t work. It never does. That’s just cognitive development, plain and simple. You can’t teach somebody two cognitive steps above from where you are—and knowing that helped me with my own children as well as with the fifth graders I taught later on. I kept telling them, like a mantra: One step at a time.

Design as a form of communication

From elementary school on, even up to starting Apple and beyond, I used my clever designs as an easier, more comfortable way to communicate with others. I believe all of us humans have an internal need to socialize. In my case, it came out mainly by doing impressive things like electronics and incredibly showy and clever things like pranks.

It was probably the shyness thing that in the sixth grade and afterward put me on the hunt for electronics journals. That way, I could read about electronics stuff without having to actually walk up to someone and ask questions. I was too shy to even go to a library and ask for a book on computers called Computers. And because I was way too shy to learn the ordinary way, I ended up getting what was to me the most important knowledge in the world accidentally.

Serendipity

Losing my Pinto changed my life completely. One of the major parts of my life at Berkeley was taking groups of people down to Southern California or even as far south as Tijuana, Mexico, on weekends. Actually, my first thought after the crash wasn’t, Oh, thank god I’m alive, but Man, now I’m not going to be able to take my friends on wild adventures anymore.

The car crash was the main reason that, after this school year, my third year at Berkeley, I went back to work instead of coming back to school. I needed to earn money, not just for the fourth year of college but also for a new car. If I hadn’t gotten in the car accident that year, I wouldn’t have quit school and I might never have started Apple. It’s weird how things happen.

Why don’t we build and then sell the printed circuit boards to them?

The Big Idea

By Thanksgiving of 1975, Steve had been to a few of the Homebrew meetings with me. And then he told me he’d noticed something: the people at Homebrew, he said, are taking the schematics, but they don’t have the time or ability to build the computer that’s spelled out in the schematics.

He said, “Why don’t we build and then sell the printed circuit boards to them?” That way, he said, people could solder all their chips to a printed circuit (PC) board and have a computer in days instead of weeks. Most of the hard work would already be done.

“His idea was for us to make these pre-printed circuit boards for $20 and sell them for $40. People would think it was a great deal because they were getting chips almost free from their companies anyway.”

“Frankly, I couldn’t see how we would earn our money back. I figured we’d have to invest about $1,000 to get a computer company to print the boards. To get that money back, we’d have to sell the board for $40 to fifty people. And I didn’t think there were fifty people at Homebrew who’d buy the board. After all, there were only about five hundred members at this point, and most of them were Altair enthusiasts.”

“But Steve had a good argument. We were in his car and he said—and I can remember him saying this like it was yesterday: “Well, even if we lose our money, we’ll have a company. For once in our lives, we’ll have a company.”

For once in our lives, we’d have a company. That convinced me. And I was excited to think about us like that. To be two best friends starting a company. Wow. I knew right then that I’d do it. How could I not?”

Eventually Steve, Ron, and I figured out a partnership agreement that started Apple and included all three of us. Steve had 45 percent, I had 45 percent, and Ron got 10 percent. We both trusted him as someone who’d be able to resolve arguments. Ron started working on the paperwork.

Buying out Ron Wayne for $800

We were participating in the biggest revolution that had ever happened, I thought. I was so happy to be a part of it. It didn’t have to be a big business. I was just having fun. Ron Wayne, the third partner, wasn’t having as much fun, I guess. He was used to big companies and big salaries. We bought him out for $800 after we delivered some of the first boards to Paul Terrell and well before we got our first outside investment.

Growing Fast

From 1,000 units a month, suddenly we went to 10,000 a month. Good god, it happened so fast. Through 1978 and 1979 we just got more and more successful. By 1980 we were the first company to sell a million computers. We were the biggest initial public offering since Ford. And we made the most millionaires in a single day in history up to that point.

There’s a big difference between just thinking about inventing something and doing it. So how do you do it? How do you actually set about changing the world?

Well, first you need to believe in yourself Don’t waver. There will be people—and I’m talking about the vast majority of people, practically everybody you’ll ever meet—who just think in black-and-white terms. Most people see things the way the media sees them or the way their friends see them, and they think if they’re right, everyone else is wrong.

So a new idea—a revolutionary new product or product feature—won’t be understandable to most people because they see things so black and white. Maybe they don’t get it because they can’t imagine it, or maybe they don’t get it because someone else has already told them what’s useful or good, and what they heard doesn’t include your idea.

Don’t let these people bring you down. Remember that they’re just taking the point of view that matches whatever the popular cultural view of the moment is. They only know what they’re exposed to. It’s a type of prejudice, actually, a type of prejudice that is absolutely against the spirit of invention.

Grayscale Thinking

But the world isn’t black and white. It’s grayscale. As an inventor, you have to see things in grayscale. You need to be open. You can’t follow the crowd.

Forget the crowd

Forget the crowd. And you need the kind of objectivity that makes you forget everything you’ve heard, clear the table, and do a factual study like a scientist would. You don’t want to jump to conclusions, take a position too quickly, and then search for as much material as you can to support your side. Who wants to waste time supporting a bad idea? It’s not worth it, that way of being stuck in your ego. You don’t want to just come up with any excuse to support your way.

Outside of the box thinking

The only way to come up with something new—something world-changing—is to think outside of the constraints everyone else has. You have to think outside of the artificial limits everyone else has already set. You have to live in the gray-scale world, not the black-and-white one, if you’re going to come up with something no one has thought of before.

Self-Doubt

It’s so easy to doubt yourself, and it’s especially easy to doubt yourself when what you’re working on is at odds with everyone else in the world who thinks they know the right way to do things. Sometimes you can’t prove whether you’re right or wrong. Only time can tell that. But if you believe in your own power to objectively reason, that’s a key to happiness.

Trust your Intuition

And a key to confidence. Another key I found to happiness was to realize that I didn’t have to disagree with someone and let it get all intense. If you believe in your own power to reason, you can just relax. You don’t have to feel the pressure to set out and convince anyone. So don’t sweat it! You have to trust your own designs, your own intuition, and your own understanding of what your invention needs to be.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

1 Comment

Pingback: 50 Biography Reading Challenge. | Lanre Dahunsi