Self-schema refers to the thoughts people have about themselves in different areas of life—a sort of mental blueprint of who they are, what they can do, and how they think others perceive them. Think of a self-schema as cognitive scaffolding or a self-stereotype—how your thoughts are assembled about aspects of yourself.

“Athletic self-schema is the cognitive scaffolding of thinking and feeling like an athlete.”

You have self-schema about many different spheres of your life—your identity as a romantic partner, as an employee or student, as a parent, a friend, an athlete, or whatever. All these identities feed into your broader “self-concept,” an overall sense of who you are, what your attributes are, and what and why certain things are important to you.

“The strength of your overall self-concept is determined by the relative importance you give to each of your identities.”

Predictably, your individual self-schemas are interconnected—they talk to one another. After all, thoughts and feelings don’t exist in a vacuum. Feeling crappy or amazing about one aspect of your life can contaminate your other identities. It’s quite unusual to find athletes who suffer from self-schema knots in only one aspect of their lives. This is actually good news because it means that improving the way you think and feel about yourself as an athlete can have a positive knock-on effect in other areas of your life too.

Your athletic self-schema develops from memories of your experiences but is also influenced by expectations of what you think your future self will be like in certain situations. For example, your self-schema as a runner would likely be strong if you ran track and cross-country in college, but you might also have a basic self-schema of being a triathlete even if you’ve never been one. Why? Because you know the discipline and commitment needed to be an athlete and you currently swim and bike to keep fit. In areas where you have little or no experience or you’re simply indifferent, you might have no schema at all.

Your self-schema shapes your expectations of what you think you can do, what you attempt and persist at, how you explain your success and failure, and how you want others to see you in certain areas of life.

Understanding an athlete’s self-schema is important because it helps us make predictions about the sorts of situations that are likely to feel stressful, challenging, and rewarding to you and, critically, what things we need to focus on to help you improve confidence and grit, take responsibility, and learn acceptance skills (“owning it”). This means that building a mature athletic identity requires that your athletic self-schema is relatively free of bugs and gremlins.

Your athletic identity is not about your speed, placings, leanness, or amount of training. A mature athletic identity is simply a special configuration of thoughts about emotions.

Athletic Identity

Athletic identity is all about thinking and feeling like an athlete. Athletic identity has nothing to do with how fast you are, how much racing you do, or how much you train. Although these details can all be signs of having a mature athletic identity, they’re certainly not required. We develop our inner and outer athletic identities when we do endurance sports—we learn skills and techniques, we develop fitness, and we interact with fellow athletes. A sign that our internal athletic identity is maturing is our use of the sport to define our athleticism. I’m a triathlete. I’m a CrossFit® athlete. I’m a runner. A sign that our outer athletic identity is getting stronger comes when we notice others are calling us that too.

“Changing your self-schema is an inside-to-out strategy (targeting thoughts to change feelings to change actions)”

Personal Experience: My Marathon Journey

I started my marathon running adventure in 2013 after losing my closest cousin, and I was looking for an outlet for the pain, grief and disillusionment I was experiencing in that period of my life. I stumbled upon a marathon race in two months and participated in much training. My time for my first marathon was 5 hours plus, and it was tough, even brutal, at the time. I ran, walked, limped, but I ultimately finished. In the past ten years, I have since run 25+ full marathons, with fifteen full marathons finished in the past two years. I ran six full marathons in 2022 and nine full marathons in 2023. My journey to developing my Athletic Identity and Self-schema has not been smooth. It has been filled with ups and downs, self-doubt, failures, dejection, triumphs, insights, personal records and self-confidence.

One of the identities that I have developed in the past ten years that I am most proud of is being a reader (life-long learner) and a runner. I run multiple marathons yearly, not because I have to but because I love the lessons I learn and the person I am becoming as a result of participating in these marathons. I have learned more from my ten years of experience running marathons than my over 3 decades of formal schooling. Marathon running has helped me become more precise in my self-schema, and developing an identity as an athlete and go-getter makes it worthwhile.

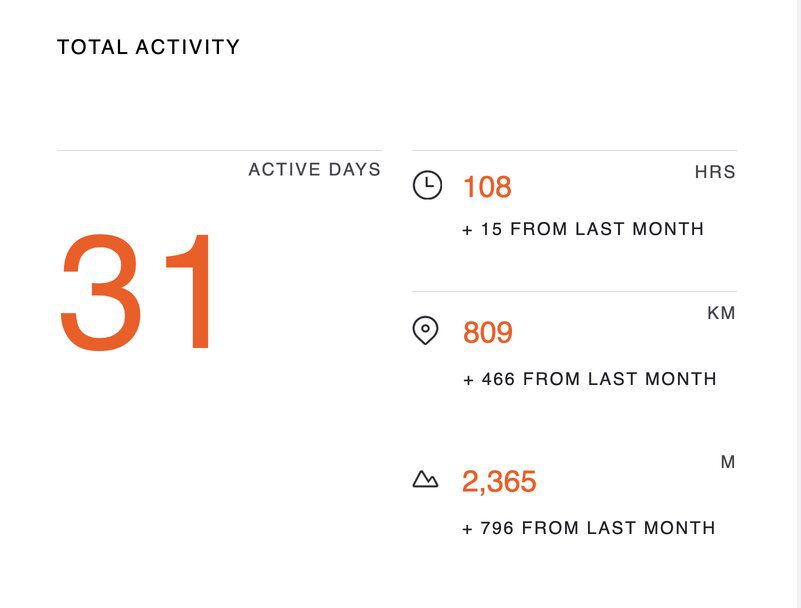

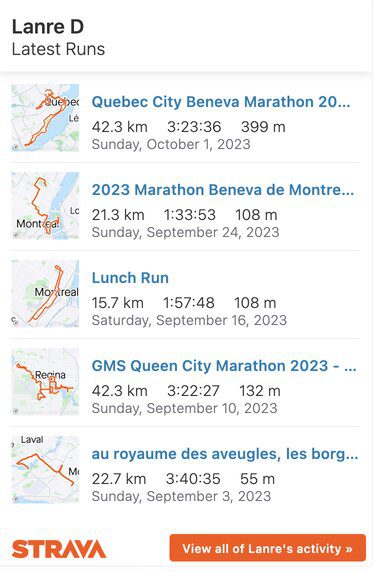

I reduced my full marathon personal best time from 3 hours 44 minutes to 3 hours 20 minutes last year at the 2023 GMS Queen City Marathon in Regina, Saskatchewan. It was a great moment, as I had been training hard before breaking my record. I had logged 108 hours of cross-training time in the gym and also ran almost every day in July covering a distance of 809 KM. By breaking this record, I had a renewed resolve that I could achieve anything that I set my mind to do.

One of the great lessons learned from running multiple marathons is the value of hardwood and preparation. As the saying goes, you can outplay your training. We play the way we train. The marathon is a great metaphor for life as your input ultimately determines your output. If you training at a sub-3 hours marathon time in training, executing during race day is not going to be hard. By running these multiple marathons, I have a clear self-schema that makes me believe I could run a time that I have trained for and can execute,

Since breaking the sub-3:30 marathon time, I have run three full marathons with great times:

- Beneva Quebec City Marathon | Quebec | October 1st, 2023 | 3;20:59

- Royal Victoria Marathon | British Columbia | October 8th, 2023 | 3:31:15

- Prince Edward Island Marathon | Charlottetown | October 15, 2023 | 3:25:13

My self-schema is changing because I am putting in the work. I intend to run a sub-3-hour marathon time in 2024. I know it will be tough, but I know what to do. Put in the same amount of time, energy, commitment, and dedication as I did in reducing my personal best by 24 minutes in 2023. Remember where I started in 2013, not athletic to clocking 854 hours of training time in 2023. It took over a decade to define my self-schema and develop my athletic identity.

The story’s moral: You don’t have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great. To achieve any goal whether it is running a marathon, writing a book, learning a foreign language, becoming financially independent or learning a programming language, one has to keep pushing and never doubt yourself. To achieve my sub-3 hour marathon goal, I will have to recalibrate my self-schema as someone who can run a sub-3 hour marathon.

You don’t have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.