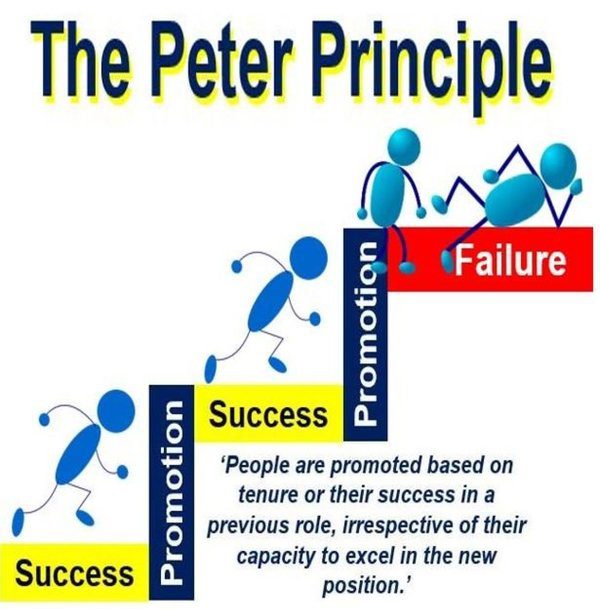

Challenge the belief that the selection of a candidate for promotion should be based on their performance in their current role, rather than on their ability relevant to the intended role.

The Peter principle is a concept in management developed by Laurence J. Peter, which observes that people in a hierarchy tend to rise to their “level of incompetence”: an employee is promoted based on their success in previous jobs until they reach a level at which they are no longer competent, as skills in one job do not necessarily translate to another.

The Peter principle states that a person who is competent at their job will earn promotion to a more senior position which requires different skills. If the promoted person lacks the skills required for their new role, then they will be incompetent at their new level, and so they will not be promoted again.

But if they are competent at their new role, then they will be promoted again, and they will continue to be promoted until they eventually reach a level at which they are incompetent. Being incompetent, they do not qualify to be promoted again, and so remain stuck at that final level for the rest of their career (termed “Final Placement” or “Peter’s Plateau”).

In a Hierarchy: Every Employee Tends to Rise to His Level of Incompetence

In their book, The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong, Dr. Laurence J Peter and Raymond Hull talks about the Universality of Occupational Incompetence::

Occupational incompetence is everywhere. Have you noticed it? Probably we all have noticed it.

We see indecisive politicians posing as resolute statesmen and the “authoritative source” who blames his misinformation on “situational imponderables.”

Limitless are the public servants who are indolent and insolent; military commanders whose behavioral timidity belies their dreadnaught rhetoric, and governors whose innate servility prevents their actually governing.

In our sophistication, we virtually shrug aside the immoral cleric, corrupt judge, incoherent attorney, author who cannot write and English teacher who cannot spell.

At universities we see proclamations authored by administrators whose own office communications are hopelessly muddled; and droning lectures from inaudible or incomprehensible instructors.

This outcome is inevitable, given enough time and assuming that there are enough positions in the hierarchy to which competent employees may be promoted.

In time, every post tends to be occupied by an employee who is incompetent to carry out its duties.

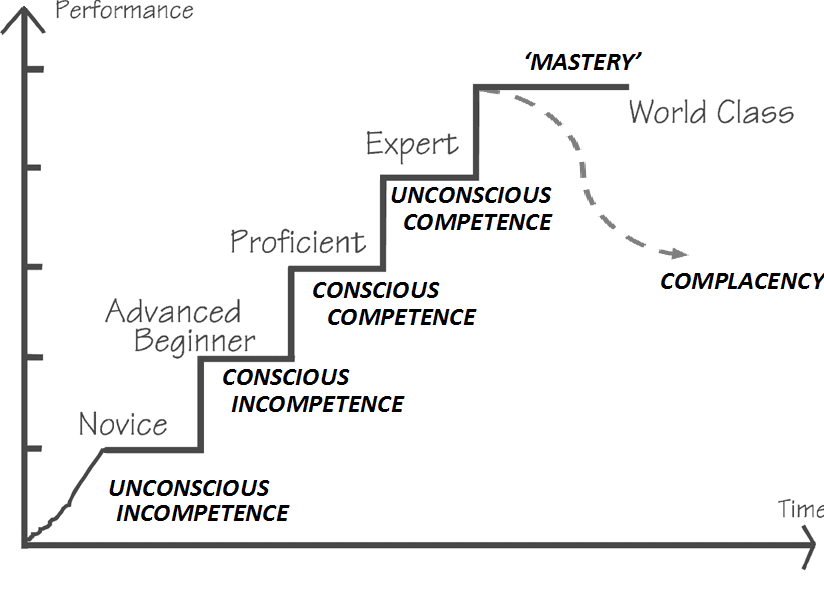

The Peter Principle levels are as follows.

- Unconscious incompetence: Someone who doesn’t know how to do something, but are totally oblivious to the fact that they don’t know this.

- Conscious incompetence: They now know what it is they need to do, and start to appreciate the gap in their competence.

- Conscious competence: Now they can do what it is they need to do, but have to give it a lot of thought and effort.

- Unconscious competence: At last they can perform a skill easily without giving it a great deal of thought or effort.

- Unconscious incompetence: The danger with doing things without thought or effort is that complacency might set in and result in a return to the first level.

Work is accomplished by those employees who have not yet reached their level of incompetence.

Peter and Hull argue that the value of the principle for managers is an understanding of why staff may reach and stay at one of these levels, or reach the highest level and then return to a lower level due to complacency in the role.

In their book, The Little Book of Big Management Theories: … and how to use them, James McGrath and Bob Bates shares ways of using the peter principle:

The usefulness of this theory is in challenging the belief that the selection of a candidate for promotion should be based on their performance in their current role, rather than on their ability relevant to the intended role. Here are six ways to beat the Peter Principle:

- Don’t fall into the trap of believing that competence in someone’s current role suggests they will be competent in a higher-level role.

- Match the person’s capabilities with the demands of the job. Your starting point should be an analysis of the skills required to achieve success in the new role.

- Talk to employees about their career expectations and interests about holding a higher position. This will help in analyzing where they would like to see themselves and whether they are satisfied with their current role or not. In this way, they won’t be compelled to do something that they are not comfortable about.

- Realise that it’s not always necessary to promote employees who are good in their existing jobs. Sometimes, without any significant change in their responsibilities, you can reward them for their hard work by offerings other incentives.

- Don’t be afraid of demoting or sacking people who have reached their level of incompetence. This may sound harsh but it can be a win-win situation because the individual who is at their level of incompetence may welcome an opportunity to return to what they did well (provided there is a face-saving way to do it).

- If you have promoted an individual and discover that they are not competent at that level, additional training, mentoring or shadowing someone who is competent may give them the tools they need to succeed.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

1 Comment

Pingback: Happened to me, moved from a job where I felt like a god to another one beyond my skills where I had constant panic attacks and where I was terrified all the time. Depends a lot on your personality, for me everything started to get much better when they t