I am an empath to the core, and I tend to see people as who they can become and not what they are presently. One of the challenges of seeing the best in people all the time is that, at some point, they begin to take it for granted, misuse the privilege or not understand my motive. One of my core personal philosophies is to give what I want. When I want money, I give it out; when I need encouragement, I inspire others; and when I want strength, I stay to give others strength. One of the hardest things to do in life is to try to change people. Leadership author John C. Maxwell observed that there are three catalysts for change: People change when they hurt enough that they have to change. People change when they learn enough that they want to change. People change when they receive enough that they are able to change.

People change when they hurt enough that they have to change. People change when they learn enough that they want to change. People change when they receive enough that they are able to change. – John C. Maxwell

One of the other unintended consequences of trying to impact people is advice-giving. I read a lot, and I am always looking for ways to become a better version of myself. When I interact with other humans, I tend to overshare what I have learnt from books with them without considering that they are at different levels of consciousness and awareness in their life journey. Most times, when we are trying to change people who are not ready for change, they eventually resist, resent and rebel against us. One of the most challenging lessons I have had to learn is to let people be because we all change when we are ready and have had enough pain. Sometimes, we must let people make the change decision themselves, make mistakes, and live with the consequences of the action and inaction.

“We must all suffer from one of two pains: the pain of discipline or the pain of regret. The difference is discipline weighs ounces while regret weighs tons.” – Jim Rohn

Change Yourself

When I was a young man, I wanted to change the world. I found it difficult to change the world, so I tried to change my nation. When I found I couldn’t change the nation, I began to focus on my town. I couldn’t change the town and as an older man, I tried to change my family.

Now, as an old man, I realize the only thing I can change is myself, and suddenly I realize that if long ago I had changed myself, I could have made an impact on my family. My family and I could have made an impact on our town. Their impact could have changed the nation and I could indeed have changed the world.”

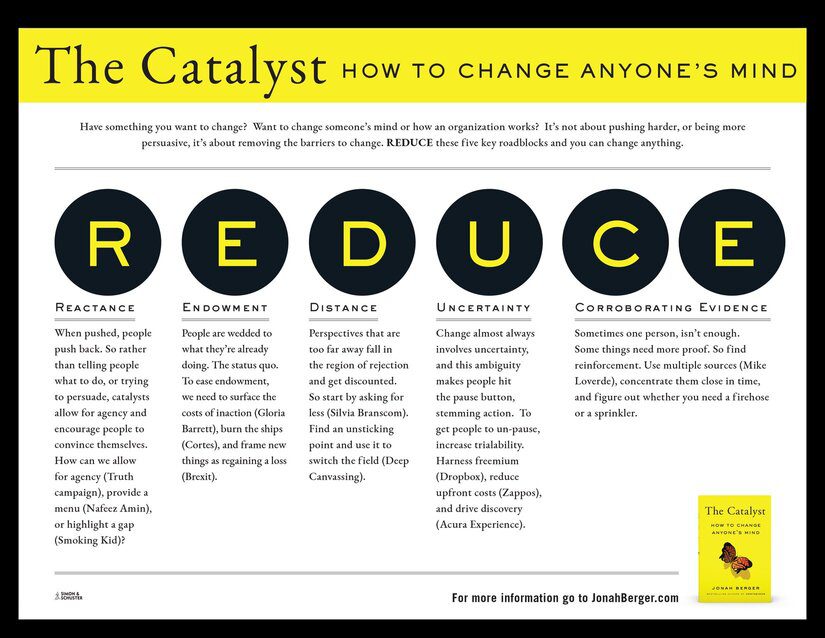

In The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind 1, Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Professor Jonah Berger shares a great framework for effecting change – REDUCE (Reactance, Endowment, Distance, Uncertainty, and Corroborating Evidence. Berger asserted that successful change isn’t about pushing harder or exerting more energy. It’s about removing barriers. Overcoming resistance by reducing friction and lowering the hurdles to action.

The five ways to be a catalyst can be organized into an acronym. Catalysts

- reduce Reactance,

- ease Endowment,

- shrink Distance,

- alleviate Uncertainty, and

- find Corroborating Evidence.

Change is hard

We persuade and cajole and pressure and push, but even after all that work, often nothing moves. Things change at a glacial pace if they change at all. People like to feel they have control over their choices and actions that they have the freedom to drive their own behavior. When others threaten or restrict that freedom, people get upset. When told they can’t or shouldn’t do something, it interferes with their autonomy. Their ability to see their actions as driven by themselves. So they push back: Who are you to tell me I can’t text while driving or walk my dog on that pristine patch of grass? I can do whatever I want!

People like to feel they have control over their choices and actions that they have the freedom to drive their own behavior.

Principle 1: Reactance

Pushing, telling, or just encouraging people to do something often makes them less likely to do it.

When pushed, people push back. Just like a missile defense system protects against incoming projectiles, people have an innate anti-persuasion system. Radar that kicks in when they sense someone is trying to convince them. To lower this barrier, catalysts encourage people to persuade themselves.

Restriction generates a psychological phenomenon called reactance. An unpleasant state that occurs when people feel their freedom is lost or threatened

Principle 2: Endowment

Change is hard because people tend to overvalue what they have: what they already own or are already doing.

As the old saying goes, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. People are wedded to what they’re already doing. And unless what they’re doing is terrible, they don’t want to switch. To ease endowment, or people’s attachment to the status quo, catalysts highlight how inaction isn’t as costless as it seems.

Whenever people think about changing, they compare things to their current state. The status quo. And if the potential gains barely outweigh the potential losses, they don’t budge.

Principle 3: Distance

Start with a place of agreement and pivot from there to switch the field. Connecting to these parallel directions should move them enough to see the initial topic differently.

People have an innate anti-persuasion system, but even when we just provide information, sometimes it backfires. Why? Another barrier is distance. If new information is within people’s zone of acceptance, they’re willing to listen. But if it is too far away, in the region of rejection, everything flips. Communication is ignored or, even worse, increases opposition.

People search for, interpret, and favor information in a way that confirms or supports their existing beliefs.

Principle 4: Uncertainty

People are risk-averse. They like knowing what they are getting, and as long as what they are getting is positive, they prefer sure things to risky ones. Even if the risky choice is better, on average.

Change often involves uncertainty. Will a new product, service, or idea be as good as the old one? It’s hard to know for sure, and this uncertainty makes people hit the pause button, halting action. To overcome this barrier, catalysts make things easier to try. Like free samples at the supermarket or test drives at the car dealership, reducing risk by letting people experience things for themselves.

Principle 5: Corroborating Evidence

If one person says you have a tail, you laugh and think they’re crazy. But if three people say it, you turn around to look.

Sometimes one person, no matter how knowledgeable or assured, is not enough. Some things just need more proof. More evidence to overcome the translation problem and drive change. Sure, one person endorsed something, but what does their endorsement say about whether I’ll like it? To overcome this barrier, catalysts find reinforcement. Corroborating evidence.

As John C. Maxwell often said “People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.” To help people change, they need to feel that we sincerely care about them and want the best for them. Most times when people decide not to change, it is not that what we are recommending for them is necessarily bad but we don’t have enough influence with them.

Holley Humphrey 2 identified some common behaviours that prevent us from being sufficiently present to connect empathically with others. The following are examples:

- Advising: “I think you should … ” “How come you didn’t … ?”

- One-upping: “That’s nothing; wait’ll you hear what happened to me.”

- Educating: “This could turn into a very positive experience for you if you just … ”

- Consoling: “It wasn’t your fault; you did the best you could.”

- Story-telling: “That reminds me of the time … ”

- Shutting down: “Cheer up. Don’t feel so bad.”

- Sympathizing: “Oh, you poor thing … ”

- Interrogating: “When did this begin?”

- Explaining: “I would have called but … ”

- Correcting: “That’s not how it happened.”

Become a Lighthouse

Consider a lighthouse. It stands on the shore with its beckoning light, guiding ships safely into the harbor. The lighthouse can’t uproot itself, wade out into the water, grab the ship by the stern, and say, “Listen, you fool! If you stay on this path, you may break up on the rocks!

No, the ship has some responsibility for its own destiny. It can choose to be guided by the lighthouse. Or it can go its own way. The lighthouse is not responsible for the ship’s decisions. All it can do is be the best lighthouse it knows how to be. 3

“Allow people to be who they are instead of what you want them to be. Send healthy support messages like, “I’m here if you need me, but your choices—and the consequences—belong to you.”

Podcast

- Tom Papa: Comedy & The Twisting Roads Of Politics/Social Media

Comments are closed.