In Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know, Wharton’s top-rated professor, organizational psychologist and bestselling author Adam Grant explores how rethinking happens, the Value of rethinking, and adopting mental flexibility/agility. He describes how we can challenge our intuition, accept and implement criticism and establish a challenge network to push our thinking to greater levels.

The book is an invitation to let go of knowledge and opinions that are no longer serving you well, and to anchor your sense of self in flexibility rather than consistency.

Our ways of thinking become habits that can weigh us down, and we don’t bother to question them until it’s too late. Expecting your squeaky brakes to keep working until they finally fail on the freeway. Believing the stock market will keep going up after analysts warn of an impending real estate bubble. Assuming your marriage is fine despite your partner’s increasing emotional distance. Feeling secure in your job even though some of your colleagues have been laid off.

Part of the problem is cognitive laziness. Some psychologists point out that we’re mental misers: we often prefer the ease of hanging on to old views over the difficulty of grappling with new ones. Yet there are also deeper forces behind our resistance to rethinking. Questioning ourselves makes the world more unpredictable. It requires us to admit that the facts may have changed, that what was once right may now be wrong. Reconsidering something we believe deeply can threaten our identities, making it feel as if we’re losing a part of ourselves.

A Rapidly changing world

Most of us take pride in our knowledge and expertise, and in staying true to our beliefs and opinions. That makes sense in a stable world, where we get rewarded for having conviction in our ideas. The problem is that we live in a rapidly changing world, where we need to spend as much time rethinking as we do thinking. Rethinking is a skill set, but it’s also a mindset. We already have many of the mental tools we need. We just have to remember to get them out of the shed and remove the rust.

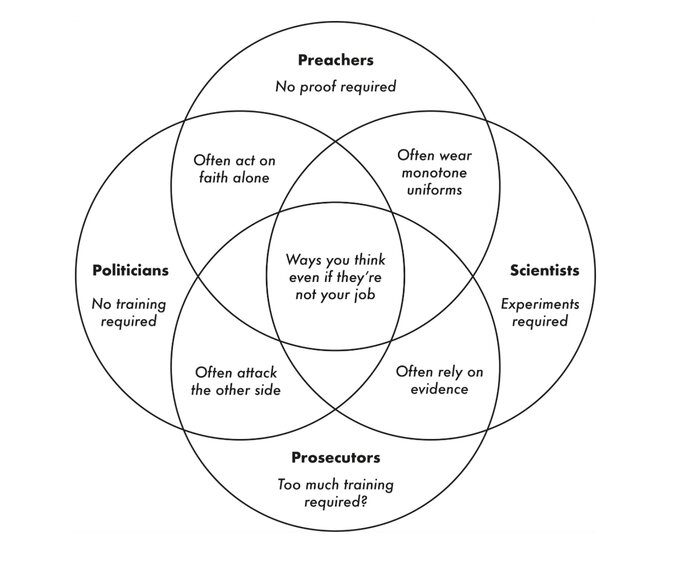

Phil Tetlock – preachers, prosecutors, and politicians Mode

As we think and talk, we often slip into the mindsets of three different professions: preachers, prosecutors, and politicians. In each of these modes, we take on a particular identity and use a distinct set of tools.

Preacher Mode

We go into preacher mode when our sacred beliefs are in jeopardy: we deliver sermons to protect and promote our ideals.

Prosecutor Mode

We enter prosecutor mode when we recognize flaws in other people’s reasoning: we marshal arguments to prove them wrong and win our case.

Politician Mode

We shift into politician mode when we’re seeking to win over an audience: we campaign and lobby for the approval of our constituents.

The risk is that we become so wrapped up in preaching that we’re right, prosecuting others who are wrong, and politicking for support that we don’t bother to rethink our own views.

In preacher mode, changing our minds is a mark of moral weakness; in scientist mode, it’s a sign of intellectual integrity. In prosecutor mode, allowing ourselves to be persuaded is admitting defeat; in scientist mode, it’s a step toward the truth. In politician mode, we flip-flop in response to carrots and sticks; in scientist mode, we shift in the face of sharper logic and stronger data.

Scientists morph into preachers when they present their pet theories as gospel and treat thoughtful critiques as sacrilege. They veer into politician terrain when they allow their views to be swayed by popularity rather than accuracy. They enter prosecutor mode when they’re hell-bent on debunking and discrediting rather than discovering.

Confirmation and Desirability Bias

In psychology there are at least two biases that drive this pattern. One is confirmation bias: seeing what we expect to see. The other is desirability bias: seeing what we want to see. These biases don’t just prevent us from applying our intelligence. They can actually contort our intelligence into a weapon against the truth. We find reasons to preach our faith more deeply, prosecute our case more passionately, and ride the tidal wave of our political party. The tragedy is that we’re usually unaware of the resulting flaws in our thinking.

All the Best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.