Hyperpolyglots are avatars of “will to plasticity.” This is the belief that we can, if we so wish, reshape our brains—and that the world impels us to do so.

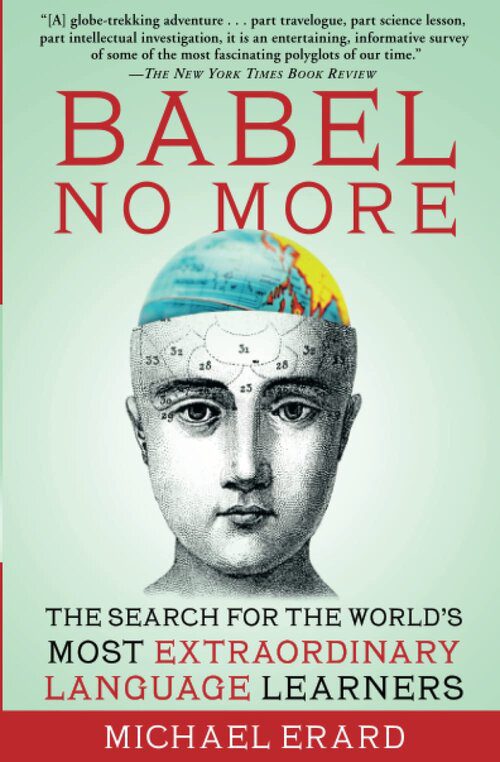

In Babel No More: The Search for the World’s Most Extraordinary Language Learners, American non-fiction writer and journalist, Michael Erard searches for language super learners and tries to make sense of their mental powers. He uncovers the secrets of historical figures like the nineteenth-century Italian cardinal Joseph Mezzofanti, who was said to speak seventy-two languages, as well as those of living language-super learners such as Alexander Arguelles, a modern-day polyglot who knows dozens of languages.

The book explores the age-old question, What are the upper limits of the human ability to learn, remember, and use languages? Erard illuminates the intellectual potential in everyone. How do some people escape the curse of Babel—and what might the gods have demanded of them in return?

The Story of Babel

In the biblical story of Babel, the people of Babel set out to build a tower to confront God in heaven. Sharing one language allowed them to communicate perfectly and move along with the construction of their tower. But God put a stop to their tower—and its arrogance—by scrambling their shared language. In the ensuing miscommunication, the humans began to disagree, the building halted, the people scattered, and the tower crumbled. In the Sumerian version of the same story, a god named Enki, jealous about humans’ fondness for another god, Enlil, cursed humans with many languages.

A language superlearner could embrace this curse of disparate languages and whisper in its ear, “Babel, no more.”

Some of the Hyperpolyglots that Erard profiled in the book include:

- Cardinal Giuseppe Mezzofanti (1774 – 1849) – Italian cardinal and famed hyperpolyglot. He was reported to speak between 72-114 languages. He was continually referred to as the pinnacle of human achievement with languages.

- Emil Krebs ( 1867 – 1930) – German diplomat, polyglot and sinologist (Chinese Studies, an academic discipline that focuses on the study of China primarily through Chinese, Philosophy, language, literature, and History. A pugnacious fin de siècle German diplomat, spoke sixty-eight languages.

- Lomb Kató (1909 – 2003) – Hungarian hyperpolyglot and one of the first simultaneous interpreters in the world. Kató taught herself Russian by reading Russian romance novels, she believed that “one learns grammar from language, not language from grammar.”

- Derick Herning, a Scotsman who grew up north of Edinburgh and now lives in the small town of Lerwick on the Shetland Islands, won the Polyglot of Europe contest after being tested in twenty-two languages.

Living Hyperpolyglots

- Alexander Arguelles – a typical day begins at 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning with him at a desk in the spare bedroom, writing in a bound book with lined pages. He writes a few pages in English to help him collect his thoughts. In his first language, he says, he’s the most expressive. Then he continues with his “scriptorium” exercise, writing two pages apiece in Arabic, Sanskrit, and Chinese, the languages he calls the “etymological source rivers.”

- Ziad Fazah – Liberian-born Lebanese polyglot, Fazah himself claims to speak 59 languages. The Guinness Book of World Records, up to the 1998 edition, listed Fazah as being able to speak and read 58 languages, citing a live interview in Athens, Greece, in July 1991.

- Helena Bozi – Works for the World Bank, studied 18 languages to an intermediate degree, and uses all the 6 languages of the world bank. She is a program evaluator for literacy programs that the world bank funds.

- Gregg Cox (the Greatest Living Linguist), according to The Guinness Book of World Records, an American named Gregg Cox lived about 170 miles away in the city of Bremen. Though Cox was credited with speaking sixty-four languages, fourteen of them fluently.

“Gregg M. Cox of Oregon, USA, the Greatest Living Linguist, is able to read, write and speak 64 languages, 11 different dialects, speaking 14 fluently.”

Johan Vandewalle – Belgian

In 1987, at the age of twenty-six, he won the Polyglot of Flanders/Babel Prize, after demonstrating communicative competence in nineteen languages.

The universality of the English Language

It’s said that on a daily basis, as many as 70 percent of all interactions in English around the world occur between non-native speakers. This means that native English speakers have less control over determining the “proper” pronunciation and grammar of English.

A hyperpolyglot is someone who speaks (or can use in reading, writing, or translating) at least six languages.

Hyperpolyglots (Gifted language learners and language accumulators)

In 1996, Dick Hudson, a professor of linguistics at University College London posted an email to a list serve for language scientists asking if anyone knew s who held the world record for the number of languages they could speak. Replies listed the names of well-known polyglots, such as Giuseppe Mezzofanti, an eighteenth-century Italian cardinal, among others.

The term Hyperpolyglot was coined by linguist Disk Hudson at University College London, who was looking for a term to capture and characterize people who spoke six or more languages. His logic was that there are communities where everyone speaks 5 languages, from the uneducated person to the most educated person.

Hyperpolyglots don’t belong to a country; they work outside of institutions—beyond even their own communities. Hyperpolyglots are a neural tribe.

Neural Tribe – Neural Hypertrophy for language learning. Environmental Selection. Sense of Identity. Personal Mission. Sub-national/extra-institutional status.

The history of culture is, in a sense, the process of uncovering certain talents while burying others—taking away the contexts that give certain abilities value. What if there were a neural tribe—a group of individuals who possess neural hardware that’s exceptionally suited for a particular activity, who have a sense of mission about undertaking the activity, and who cultivate a personal identity as someone who does that activity? Their mental ability would predate our civilization and stand outside it, though it would manifest itself according to the social and cultural makeup of the time.

What hyperpolyglots are like:

They’ve learned how to learn. They’ve discovered methods that fit them. They like – and crave – repetition. They remember what they learn. They have a feel for languages. They find or make a niche. They assert the right not to speak English.

Why do we need hyperpolyglots?

Migration is rising, tourism is increasing, Media is becoming more multilingual, English isn’t enough, new sort of multilingualism and a new condition for multilingualism.

The Geschwind-Galaburda hypothesis

The idea that because male hormones in the fetus affect the developing brain, the effects of asymmetrical development of brain hemispheres would be seen mostly in males. Females also have male hormones, but they have fewer and would be less affected.

Geschwind-Galaburda hypothesis suggests that a certain fetal environment could produce a brain that’s linguistically superior and that verbal gifts will accompany visuospatial deficits, along with other traits.

The Hyperpolyglot Secret

- Profile yourself:

What are your learning preferences? What is your cognitive style? And then going out and finding methods that work for you and prove your higher-order cognitive skills - Improve higher-order cognitive skills

Get working on that working memory trainer and executive function trainer. You could be working on a language and doing your dual-end back iPhone app on the treadmill, and the two things will arguably or theoretically enhance each other. - Psychoemotional preparation

There’s neuromodulation, managing dopamine and other kinds of things, and thinking about the role of hormones in the role of language learning.

- Manage dopamine (i.e. neuromodulate)

If you want to improve at languages, you should manage your dopamine. - Dopamine is the neurotransmitter that operates in the brain’s reward circuit. When we do certain things, a little dopamine is released in our brains, telling it that we just did something pleasurable, which ensures that we do that pleasurable thing again. People who learn many languages do it because they’re attached to the pleasure of it.

- Build community

For multilinguals, learning languages is an act of joining society. There’s no motive, no separable “will to plasticity” that’s distinct from what it means to be part of that society. Being a hyperpolyglot means exactly the opposite. The hyperpolyglot’s pursuit of many languages may be a bridge to the rest of the world, but it walls him off from his immediate language community.

Hyperpolyglots are people who have the multicompetence to belong to a real or imagined global community. - Study > 1 language

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.