Sometimes the circumstances at hand force us to be braver than we actually are, and so we knock on doors and ask for assistance.

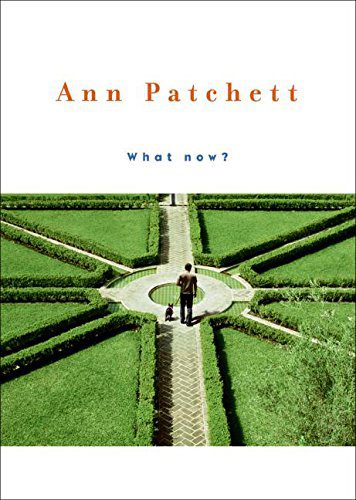

Author Ann Patchett delivered the commencement speech at Sarah Lawrence College, her alma mater, in 2006. Her speech was expanded to a book – What Now? Which contains essays on hope and inspiration for anyone at a crossroads, whether graduating, changing careers, or transitioning from one life stage to another.

If all fairy tales begin “Once upon a time,” then all graduation speeches begin “When I was sitting where you are now.” We may not always say it, at least not in those exact words, but it’s what graduation speakers are thinking. We look out at the sea of you and think, Isn’t there some mistake? I should still be sitting there. I was that young fifteen minutes ago, I was that beautiful and lost. For me this feeling is compounded by the fact that Sarah Lawrence was my own alma mater.

I look out at all these chairs lined up across Westlands lawn and I think, I slept on that lawn, I breathed that wisteria. I batted away those very same bees, or at least I batted away their progenitors. Time has a funny way of collapsing when you go back to a place you once loved. You find yourself thinking, I was kissed in that building, I climbed up that tree. This place hasn’t changed so terribly much, and so by an extension of logic I must not have changed much, either.

But I have.

That’s why I’m the graduation speaker.

Think of me as Darwin sailing home on the Beagle. I went forth in the world just the way you are about to go forth, and I gathered up all the wondrous things I’ve seen; now I’ve brought them back to you. As the graduation speaker I’m the one with the wisdom, or at least that’s the assumption, but you as the graduates have something even better: you have youth, which, especially when you multiply it by several hundred, is a thing so fulgent it all but knocks the breath out of those of us who are up on the stage. I’d like to tell you to appreciate your youth, to stop and admire your own health and intelligence, but every writer has a cliché quota and I used up mine by saying, When I was sitting where you are now.

When you leave this place, as you will in a couple of hours, be sure to come back.

Coming back is the thing that enables you to see how all the dots in your life are con-nected, how one decision leads you to another, how one twist of fate, good or bad, brings you to a door that later takes you to another door, which, aided by several detours—long hallways and unforeseen stairwells—eventually puts you in the place you are now.

Every choice lays down a trail of bread crumbs, so that when you look behind you there appears to be a very clear path that points straight to the place where you now stand. But when you look ahead there isn’t a bread crumb in sight—there are just a few shrubs, a bunch of trees, a handful of skittish woodland creatures. You glance from left to right and find no indication of which way you’re supposed to go. And so you stand there, sniffing at the wind, looking for direc-tional clues in the growth patterns of moss, and you think, What now?

The first time I reached that particular impasse in my life I was in high school, and the burning question concerning my future was where I was going to college. Every day I stood at the window watching for the mailman, and as soon as he had driven safely away (for some reason I thought it was important to conceal my eagerness from the mailman) would dart out to the box and search for the documents that would determine my fate amongst the grocery store coupons, utility bills, and promotional fliers. But not a single envelope bore my name. It seemed in those days the world only had one question for me, and it was not, How are you feeling? or What is the state of your soul? or What is it you want from life? No, the only thing anyone asked me back then was, Where are you going to college? Everywhere I went I felt as if I were being hounded by my own Greek chorus, and even though all those people hound-ing me quite possibly had good intentions and were genuinely interested in my future, after a while the questions started to feel like nothing more than a relentless interrogation: a dark room, a single chair, a blinding light in my eyes. “I don’t KNOW!” I wanted to scream. “I don’t KNOW where I’m going to college!” What if I didn’t get accepted anywhere? Didn’t they ever think about that?

What if I had to live at home forever and find a job waiting tables and never got the education I needed to be a writer? If the people who questioned me had any notion of the depth and the darkness of my fears, I doubt they would have had the temerity to ask me anything at all.

But thanks to the natural order of the universe, for better or for worse, everything eventually changes. One beautiful afternoon the mailman drove off and I ran out to the box and there it was, my entire future in one slim envelope. I ripped into it right there on the lawn and read the contents again and again until I had it committed to memory. I was going to college. In that instant everything in my world was different because I had an answer for the inevitable question. In a funny way that was even more meaningful than the acceptance itself. When the aunt and the dentist and the best friend’s mother asked me where I was going, I could reply with a level of nonchalance that made it seem there was never any doubt, “College? Why, I’m going to Sarah Lawrence.

Oh, I was set. My sense of time was so underdeveloped that four years sounded like a glorious eternity. I had gotten into the school that I wanted to go to and I would stay there and never have to worry about the future again. Finally I arrived on campus and lugged my suitcases up the stairs of the dreamy little house that was my dorm, put my toothbrush in my assigned toothbrush slot, and unpacked.

I knew I wanted to be a writer and so I thought it best to make myself well-rounded, since that’s what a writer had to be. I flipped through the course catalog and tried to choose between marine biology and comparative religion and printmaking and economics and Shakespeare. There were so many possibilities that I felt dizzy—what if I picked the wrong one? What if I missed out on the thing I needed the most just because I didn’t know I needed it? Back then I thought that a person’s education was defined by majors and minors, and that classes set down a map that would guide the rest of my life. If I took the wrong turn now would I feel the repercussions twenty years down the road?

How in the world was I qualified to make the decisions that would shape my future? I had thought so much about getting into college that I didn’t ever stop to consider what college might be like. All I wanted was to be able to hand the catalog over to my mother and ask her, What now?

I was seventeen and a long way from home, having come to New York from Tennessee. There is no way to overstate the fact that all I was in those days was terribly, terribly lonely. I don’t even know if that particular brand of loneliness exists anymore, though I suspect that new kinds have sprung up to take its place. There was no e-mail, and in those happy, bygone days only doctors and drug dealers carried cell phones. There was a pay phone downstairs, but it was prohibitively expensive, and anyway, there was always somebody parked on it, usually the beautiful girl from Caracas. We called her the Venezuelan Princess, and she had enough money to talk to her family in South America for hours on end. I went back upstairs with my little sack of quarters and wrote as many letters as I had stamps. I wrote to my parents, my grandmother, and sister. I wrote to all my far-flung girlfriends from high school, but the letters couldn’t get to their destinations fast enough for my sadness to be heard.

Ulti-mately this exercise proved as instructive to me as any writing class since this is where I learned how to transfer the contents of my heart onto a piece of paper. Each letter expressed a different aspect of my circumstances, as each was tailored to its particular reader, but none of them made me feel any better.

“Writing is good for many things, but curing loneliness isn’t one of them. From my room I heard the voices of the other fresh-men who laughed and talked as if they had all been inseparable since Montessori. There was a river full of life rushing right past my door and I didn’t have a single clue about how I might jump in.

Writing is good for many things, but curing loneliness isn’t one of them. From my room I heard the voices of the other fresh-men who laughed and talked as if they had all been inseparable since Montessori. There was a river full of life rushing right past my door and I didn’t have a single clue about how I might jump in.

In the end I did the only thing I knew how to do, the thing they always taught us to do in Catholic school: I did unto others. If you want someone to be nice to you, you must be nice to someone else, and since I really knew only one person—my newly assigned adviser Chet Biscardi, who had shown me great kindness in our first meeting—I decided I would bake him a batch of cookies.

If it sounds hokey then you can rest assured that’s because I was one seriously hokey kid. I walked into town and carried back sacks of flour and sugar and eggs. I bought pans, a measuring cup, a spatula. Because I was on every level starting from scratch those cookies were destined to be the most expensive in history. I mixed up the batter in the little kitchen downstairs in the dorm, beat in the chips and buttered the pans. I set the oven for 350 and waited for it to heat up. I waited.

After a suspiciously long time I stuck my hand in and then, feeling a chill, touched the racks. Two pans of raw cookie dough neatly arranged into balls wouldn’t have been bad eating but they would have made a very poor gift. I sat there for a minute feeling hopeless, but then decided I couldn’t, since the cookies were meant to cure my hopelessness. I picked up the sheets, fixed the bowl of extra dough beneath one arm, and went outside.

Next door was another dorm with no doubt equally pathetic appliances, but across the street was a fine-looking house. I don’t think it would be an overstatement to say it was a mansion. It was the kind of house one could be certain would have, at the very minimum, one working oven. I was a shy person, but at that moment I was on the edge. I needed a heating element. And so I marched ahead and, using one corner of a pan, knocked on the door.

Alice Ilchman often told this story herself, how during her first week as the new president, still waist-deep in boxes and settling into her house, she opened her front door to find a freshman holding two trays of unbaked cookies. She paused for a minute, wondering if this was some sort of tradition about which no one had informed her, and then she led me back to the kitchen and told me to make myself at home, the most beautiful words that anyone had spoken to me for days. In the time it took the cookies to bake and cool, I met her children and played with her dog. And maybe because I wrote a thank-you note on a paper towel and left it on the table with some cookies, I was invited back to babysit for Alice’s daughter, Sarah, and since I proved to be a reliable babysitter, I was also asked back to serve at dinner parties, and then to cook at dinner parties. After all, I clearly knew how to cook.

Had I been the most cunning freshman in the history of higher education, I doubt I could have come up with a plan that would have gotten me the very thing I longed for, which was less an oven and more a family to take me in. I never would have had the words to ask for something as large as that.

Sometimes the circumstances at hand force us to be braver than we actually are, and so we knock on doors and ask for assistance.

Sometimes not having any idea where we’re going works out better than we could possibly have imagined.

And sometimes, we don’t realize what we’ve learned until we’ve already known it for a very long time.

Comments are closed.