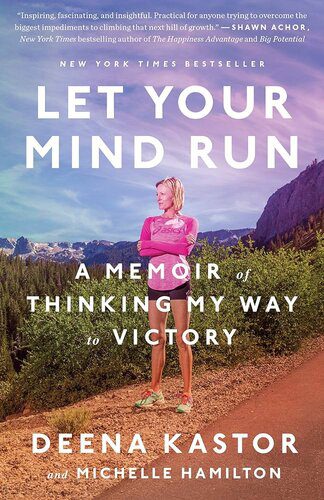

In Let Your Mind Run: A Memoir of Thinking My Way to Victory, American long-distance runner Deena Kastor takes the reader on a life journey in running. How having a positive mindset, discipline, and excellent work ethic brought her success in her running career. She also shared the rollercoaster of winning and losing, motherhood’s challenges, and her quest to balance life and running.

“I loved running right from the start. It was simple and fun. It lacked rules and structure. There was no equipment to fuss with, no technique to learn.”

Best of all, running didn’t make me feel foolish or ridiculous, like I’d done something wrong. The ease of it made me feel competent and free. Everything we were asked to do, I could do. I ran and counted my laps. I warmed up on the trails, happily shooting out the gate with my teammates to the wild open space, and ran among the rabbits and deer.

I remember thinking how lucky we runners were to be in constant motion. We were part of the action all the time. Running was also, to my surprise and delight, both solitary and social.

The power of our thought

Starting out, I had no idea running would be so mental, no idea that the most important aspect of my success would come down to how I thought. Eventually, though, I realized a good attitude went far beyond the general idea of staying positive. It was part of a discipline, a long-cultivated habit of building and sustaining a positive mind capable of turning every experience into fuel.

Positive thinking has long been considered a powerful life tool, to the point that it has almost become a cliché. Yet its great power emerges when applied as a lifelong process. Changing a single thought improved the moment I was in, but years of dedicated practice changed my career, my life, and ultimately me.

Don’t Focus on Winning

“As I ran, I replayed the call in my mind. One of the more striking observations was that Coach Vigil never mentioned winning. He also talked a lot about traits, but not one of them was talent. This unraveled everything I thought about running. Coach Vigil showed me there were multiple aspects of the sport I’d never paid attention to. A buzz of opportunity swarmed around me. ”

“Repetitio mater studiorum est: repetition is the mother of learning.”

“Sometimes Coach saw the I-don’t-think-so look on my face before the last mile repeat and said, “Repetitio mater studiorum est”—repetition is the mother of learning. Repetition of speed built power. Repetition of miles built endurance. So I launched into the repeat with that perspective, running hard, and finishing the mile a few seconds faster than the week before.”

Traits outside of Running

“It took some time, but I eventually found qualities outside of running I admired in myself: I was creative, curious, generous. I liked how I experimented with ingredients in the kitchen and was good at voicing my appreciation for others. I admired that I read books on a variety of subjects and always studied the places I was traveling to. Acknowledging these good qualities felt like a kind gesture toward myself, a means of nurturing. Had I stood in front of the mirror in that moment, I would have seen a powerful set of lungs, shoulders that drove my stride, and legs that carried me to my goals. Seeing this side of myself was its own kind of progress, one that a stopwatch might never reveal.”

Positive Affirmations and Visualization

I’d found strength in positivity, gratitude, and enjoyment. But I wanted to use everything available to further my mental preparation. So I turned to practices I’d been introduced to in high school: positive affirmations and visualization. I’d gone to a running camp at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs one year. In a session with a sports psychologist, we wrote our goals or desires as statements in the present tense. These, the psychologist said, are positive affirmations. They confirm who you’re striving to be.

The mind doesn’t distinguish between fact and fiction. What the mind sees and thinks, the body feels, and what the body feels, the mind, or at least the subconscious, learns.

Visualizing Victory

Each visualization unfolded organically. I didn’t plot it out or overthink it. I followed along as the terrain and competitors came at me. Sometimes I was in a pack, steadily moving to the front. Other times I led the race and pressed to stay in the lead. In some editions, it was hot. Other times it was raining. My hair was in a ponytail. The next day it was tucked into a hat.

Behind closed eyes I pictured their aggression drawing out the best in me. A competitor from behind pushed me to run harder. Lynn’s attempts to break me strengthened my composure and grit. Never had I run with such force as the day Amy and I ran stride for stride down the grass toward the finish. No matter the situation, I matched it with my own strength—faster reactions, quicker recoveries, a stronger push. Race after race, I won. Sometimes by as little as 2 seconds. Other times, by a 2-minute margin. But every time, I won. I didn’t want my subconscious to think that losing was possible.

Self-Belief

Seeing myself as a champion prompted me to think, and therefore act, more like one. I was already living an athlete’s life and giving my all in each workout. Affirmations, visualization, and musical associations were for me layers of reinforcement in my self-belief. That belief expressed itself in a subtle but important way in practice. I held myself in a new regard. As I ran, I did so with the confidence of a champion. A greater level of belief and determination mixed with the physical adaptations led to greater speed. In November, a month before nationals, my times dropped in most workouts: lappers, mile repeats, and tempos.

I studied Spanish and noted the acuity of mind that came from trying to think in a foreign language.

Know the game you are playing

“Walking down the finishing chute catching my breath, I felt a kinship with the women ahead of me. I had been with them, and even though I was dropped, I had been there. I’d learned the physical language of the pack, understood how it worked, and gained appreciation for the aggression required to lead. I’d moved from twenty-ninth to twentieth place on the world stage. With another year and another season of physical and mental growth, I knew I could put myself back in with the leaders, and hang on even longer.”

Loneliness of the Long-distance Runner

People are always talking about the loneliness of the long-distance runner, but these moments were why I never felt it. We were lone competitors pursuing our own dreams, and yet our singular goal united us. The intensity of the pursuit and the doubts and miles we all pushed through connected us, and these conversations were to me not just the sharing of information but intimate moments of support.

Emotional Control

“The marathon is all about endurance,” Coach said. Long interval workouts and tempo runs build stamina, but the long run was the key workout for marathon training. “You’ve never focused on endurance so you’re going to have to have a lot of emotional control, or you’ll burn yourself out in the first half of the week,” he said. “Emotional control” was Coach-speak for patience, meaning let your mind dictate your pace, not your emotions.

“The marathon is an energy game”

Going out too hard and surging wastes energy. You want to be smooth and economical.” In the long run, Coach said, we’re training the body’s energy system to more readily burn fat over carbohydrates. You see this kind of efficiency in animals that migrate long distances, he said, whales and birds notably, who glide with minimal movement, slowly releasing their energy. This efficient use of energy translated to pacing. The game of emotional control, then, was to bottle up the excitement of competition and slowly release it over the miles.

The Marathon Mind

This was where the marathon was unique. In the shorter distances, the pace was hard from the first mile to the finish and I had to use mental strategies to encourage myself the entire way. Long runs taught me the marathon mind followed a different rhythm. It moved from easy to hard to very hard. So to run it effectively, my mind had to respond to the distance’s ever-increasing challenge. In the early miles, the marathon mind needed to be calm to keep the pace controlled and I consciously enjoyed the time, taking in the views, while also keeping an eye on pace and fluids.

Around the halfway point when the pace required more effort, the internal cheerleader stepped in—the encouraging voice that pushed me in every race.

The Insistent Mind

The final miles of the long run required a whole new mental level: the insistent mind. By this point, I’d be climbing Sherwin Creek Road working to pull myself out of the valley. I thought this would be the place I’d release my bottled-up excitement. But that had been beginner’s optimism. I had nothing to uncork. My body felt a deep fatigue, nothing like the burn at the end of repeats. Just an unwavering desire to stop.

Don’t let the fatigue deceive you. There’s good and bad patches in a race and it’s your job to get out of the bad patches as quickly as possible and hang on to the good ones.

Challenging Boundaries

When racing, it was my nature to work to extend a lead. But after the marathon, my purpose changed. Competing became less about beating competitors and more about challenging my boundaries. I wanted to get myself to a place I hadn’t gone before. I had never thought of myself as someone who was afraid of the pain of racing, but now as I charged down the field during a race, I was aware of the absence of any hesitation. The marathon had so altered my perception of suffering that there was no hurt holding me back in the shorter distances.

If the marathon taught me that I could endure, it also showed me how much more there was to learn. I could push. But how could I push more? How could I get more out of my body?

Running’s simplicity was beautiful yet deceptive. If you viewed it as simply putting one foot in front of the other, you missed the nuance and synergy of the movement that leads to greater power and speed.

Focus on yourself, not the competition

I had limited myself by setting a goal based on my competitors. It was a natural thing to do. A competitor’s goal is to beat the competition. But I’d settled for achieving my goal instead of pushing toward my limit. It occurred to me that while we need a plan B to turn to when races aren’t going well, we should also have a plan when our strength exceeds our expectations.

When you’re well conditioned, when your breath and your legs are in sync, and when your mind is immersed only in the task at hand, there is nothing blocking your momentum.

The Pursuit of Joy

The more enjoyable the experience, the more effort we all put into it, and the greater the satisfaction. We were throwing more mileage and intensity at my body, and it took it. More than took it, my body thrived. I woke each morning feeling like “Let’s go!” There was a lightness in my stride and a fierceness in my limbs. To train to earn an Olympic medal is to push your body to its edge. Yet I did not feel I was moving toward the edge. I felt like I was climbing toward a peak that had no limit.

I had learned disappointment was rooted in the desire to improve and that under the grief, there was deep love. Resiliency opens doors, and compassion and gratitude can dissolve tension, and enrich any moment.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.